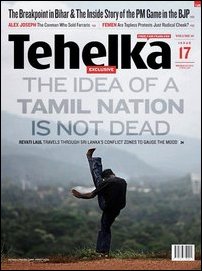

‘Idea of Tamil nation not dead despite aftermath of genocide’: Tehelka report

[TamilNet, Friday, 19 April 2013, 21:10 GMT]

Even in the aftermath of terror and genocide, the idea of nationhood has not disappeared among the Tamils in the island of Sri Lanka, writes journalist Revati Laul in an investigative feature published on the Indian news magazine Tehelka on its April 27 issue. Travelling to the militarily occupied Tamil homeland in the north and east and interacting with politicians, civil society activists, NGO workers, priests, ex-LTTE cadres and ordinary people, Ms Laul provides through their accounts a picture of the intense oppression that the Sri Lankan state is subjecting the Tamils to through various means, she further notes how the UN’s “pussyfooting on the war” and the Geneva resolution in March 2013 gave a cloak for such oppression, arguing that “It is this refusal to take in the whole narrative that allows Rajapaksa to tell the world all is well now with the Tamils in his country.”

Excerpts from Ms Laul’s article on Tehelka titled ‘The war maybe over but the idea lives on’ follows:

“The idea of a separate Tamil nation is not dead in Sri Lanka.”

“There was a time when this was espoused with brutal violence by the dreaded LTTE. That violence has been leached out now to be replaced by a kind of limitless — and perhaps more potent — despair. There are reasons why the idea of a separate Tamil nation refuses to die.”

“The chilling story of the LTTE and its lethal suicide bombers is well-known. The horrific retaliatory killing of its cadres and thousands of Tamil civilians by the Sri Lankan Army towards the end of the war is also now an emerging story. But this is a report on the silent war that continues till this day against the Tamils, an insidious and systematic violence they call a “structural genocide”.”

“With the war over, things have gone back to usual. Contrary to Rajapaksa’s famed 13th amendment, promising autonomy to the provincial councils in the north for the Tamils, this means a return to State policies from the 1950s that systematically and deliberately excluded them from cultivable farmland and prime fishing waters. The exclusion that sparked the Tamil resistance and war in the first place is back with a bang.”

“Trincomalee in the east, a long and beautiful stretch of coastline once held by the LTTE, is now back on the tourist map after it was recaptured by the army in 2006. But Trincomalee is overrun with soldiers at every street corner. Every passenger on every incoming bus to the north and east is checked by the military. Every time you board a bus, you have to write your contact numbers, purpose of visit and passport details.”

A report in the Economic and Political Weekly on 14 July 2012 claimed the ratio of army to civilians in these parts is as high as 1:5. If that’s true, it’s at least four times more than the troops on ground in Afghanistan where a war is still on. Sri Lankan Army spokesperson Brigadier Ruwan Wannigasooriya calls the figures preposterous. According to him, not more than 6,000 personnel are deployed in Trincomalee. For instance, the reason they check each bus, he says, is “in case former LTTE cadre are carrying weapons on them”.

“In Thennavanmarapuady, an ancient Tamil village in Trincomalee, the underlying reasons for the seemingly irreparable hostility between Tamils and Sinhalese becomes even more apparent. The village traces its antecedents to the 9th century, when a Pandian king conquered the area. The Pandian dynasty ruled large parts of Tamil territory in ancient India and northern Sri Lanka. In the 1980s, this land became the theatre of conflict between the LTTE and the Sri Lankan government. Its people, therefore, fled to a camp in Mullaitivu in the north. From here too, they moved many times; some fled to India.”

“After the civil war ended in 2009, these farmers wanted to return to their homes and the 1,200 acres of paddy fields they had left two decades earlier. After many difficult rounds of negotiation with the local government, families began to get permits to come back in batches. But they returned to find their land overrun by the army. Nearly 150 families are back in the area now but they live in temporary camps built by the UNHRC in 2011. Instead of 1,200 acres, they are now collectively left with a mere 150 acres to cultivate. An additional 150 acres is now occupied by Sinhalese farmers.”

“Complaints to the police have led nowhere. The head of the society they have formed has written directly to President Rajapaksa as well as every bureaucrat in between, to no avail. A farming community that, at the time of fleeing their land in 1984, made the equivalent of LKR 50,000 a month now earns not more than LKR 2,000, which for a war-inflated economy is barely subsistence level.”

“According to the government, most Tamils dislocated by decades of civil war — and the last devastating push by the Sri Lankan Army — have been resettled. But an NGO working with displaced people explains what “resettled” really means. Farmers who once had one-acre plots are “resettled” on pint-sized slices of land measuring 0.125 acres. “It’s part of a State sponsored design to resettle Tamils at below subsistence levels so they can never regroup and fight,” the NGO explains.

“Reliable figures for the thousands of people displaced by war and still living in camps are hard to come by. Tamils here say, like everything else, the flow of information is tightly controlled by the government and scripted to suit the story they want the world to hear. The scale of displacement and dispossession, therefore, can only be hazarded from reports like this one, based on patchwork anecdotes from the ground.”

“Looking at these stories of torture as merely a humanitarian crisis, however, is to miss the big picture. It makes activist lawyer K Guruparan very angry. “A simple human rights discourse doesn’t help,” he explains. It merely forces people to weigh one set of atrocities against another — those by the Sri Lankan Army in 2009 against those carried out over the past 30 years by the LTTE, which had one of the deadliest guerrilla armies and suicide squads in contemporary history. “Without the history of Tamil oppression and the ongoing structural genocide, the story of the Tamils has almost no meaning,” says Guruparan. “You have to look at the longstanding process of disenfranchisement from which the LTTE emerged.””

“The language of terror paints absolutist pictures that remove the possibility of context and history. Despite the barbaric scale of Tamil civilian killings — 40,000 in the last six months of the army push in 2009 is the official estimate — it allows the Sinhalese majority to revere President Rajapaksa. It also allows international actors like the UNHRC, the US and Indian governments to take ambivalent positions on what happened.”

“Consider the UN’s pussyfooting on the war, for instance. In March 2011, a report from the UN Secretary General’s office said: “Between September 2008 and 19 May 2009, the Sri Lankan Army advanced its campaign into the Vanni where the army used large-scale and widespread shelling, causing a large numbers of civilian deaths.” The report further spelled out how the army had shelled no-fire zones, UN hubs and hospitals and internally-displaced Tamils.”

“Two years later, however, on 19 March this year, when the UNHRC drafted a resolution on Sri Lanka, it seemed to have developed amnesia about this report. The resolution was gentle in its censure of the government for what happened in 2009 and even praised it for the work done since — “welcoming and acknowledging the progress made by the government of Sri Lanka in rebuilding infrastructure, demining, and resettling the majority of internally displaced persons”.”

“It is this refusal to take in the whole narrative that allows Rajapaksa to tell the world all is well now with the Tamils in his country.”

“In 2011, a document called ‘The Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Report’ was published. It was deemed independent but conducted by people appointed by the Sri Lankan government. It listed that the security forces had lost 5,556 personnel between July 2006 and May 2009 and 28,414 were injured. The LTTE, on the other hand, had lost 22,247 of its cadre. It spoke of the “principle of proportionality” and cited instances of war crimes from the Bosnian war to make the point that the blame for atrocities against Tamils in the war was a relative question.”

“Among all the Sri Lanka’s living dead that TEHELKA met, perhaps the most difficult to face were those whose families have gone missing since the end of the war. The war over statistics and narratives is even starker when it comes to the missing. For instance, a group of pastors sent a report to the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission that put the figure of those missing from two districts in the north, where most of the Tamils had converged at the end of the war, at 1,46,679. They said they had used government data to arrive at this number, based on the population count in October 2008 and May 2009.”

“Not surprisingly, the army spokesperson rubbished the figures. He cited figures compiled by government schoolteachers and village-level officials. This report puts the figures of “those untraceable” across four districts of the north from 2005 to 2009 at 4,156.”

“Catholic priests in the north and east are faced with the fact that their church is divided straight down the middle. With Catholic Tamils on one side — the victims. And the Sinhalese Catholics on the other — who have thrown their weight behind the rest of the Sinhalese — the victors.”

“Priests have stepped in to help victims walk with fear every day. They take different routes while travelling, delete call history from their cell phones and despite that, receive regular calls and threats from the CID.”

“The Tamil media is equally under threat. At the crack of dawn on 3 April, Aramugham Ponaraja, the office manager at the Udayan daily in Kilinochchi, was getting ready to distribute the first batch of newspapers when six masked goons attacked him 17 times with cricket stumps.”

“Tamil MP Sivagnanam Sritharan’s office was attacked just a few days before that by similarly masked goons. Under normal circumstances, the string of attacks may have been completely unconnected. In the times Tamils live in now, all attacks point only to one place — Sinhalese mobs asserting power over the vanquished.”

“Like how East Timor separated out of Indonesia in 2002, after the intervention of the UN, to become Timor Leste. The intervention was the result of incessant lobbying by the East Timorese and a truth and reconciliation commission. The territory was administered by the UN from 1999 until 2012, when it was finally handed over to an independent government. The Tamils are now trying to get their version of the truth out. And given the history of violence and broken promises, most say, reconciliation is not an option.”

“They say their window of hope for now is twofold: India and the US — two countries that should be scared at the increasing proximity of the Sri Lankan government with China and Pakistan. Does India want the strong presence of Pakistan and China less than 5 km away from its southern coast, they ask. And they hope that the US will have similar fears and decide to back their cause. For now, that is their only recourse.”

“Former Tamil MP Ponnambalam puts it simply: “I think it’s dangerous for us to think about what is possible. If we start thinking about that, it only means assimilation. We must stop talking Tamil, we must give up our religion. We must be Sinhalese and Buddhist.””

“Over and above the geopolitics and domestic Tamil politics that directly affects India, the Sri Lankan Tamils’ story raises a disturbing question. Can the desperate and continuing plight of a people be explained away by terrorism alone? For now, more than 22 lakh Tamils within Sri Lanka and an estimated 10 lakh in the diaspora, are asking this universally perplexing question. As their story also serves as a warning to other displaced people without a nation — while the world and the UN plays a double game, your idea of nationhood could be the next to disappear.””

“But even in the aftermath of the terror and genocide, the Tamil idea of nationhood has not disappeared. If India does not want another cycle of violence at its doorstep, it cannot afford to be indifferent to the voices of the Lankan Tamils.”

Chronology:

External Links: