Monks and soldiers trod war road together

[TamilNet, Sunday, 05 September 1999, 23:59 GMT]

A Sri Lanka Army (SLA) soldier was killed and three security forces personnel, including a captain, were seriously wounded when a military vehicle in which they were travelling was hit by a claymore mine blast at Madathadi Atchuvely, Jaffna around 4.30 p.m. today. Two Buddhist priests who were in the bus were also injured in the blast.

The wounded soldiers and Buddhist priests were taken to the Manthikai hospital and from there they were rushed to the SLA's military base complex at Palaly in the Manthikai hospital's ambulance.

The priests had come to Nainathivu, an island off the peninsula, and had wanted to buy grapes in Atchuvely where they are going cheap due to the inability of growers to market them outside Jaffna. SLA had hence brought them in the army vehicle to purchase grapes.

The vehicle was on its way back with the Buddhist priests and soldiers when it was hit by the claymore explosion sources said. It had joined an army convoy passing that way said sources.

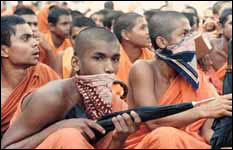

The Sri Lankan Army is predominantly Sinhala Buddhist. All its official ceremonies are officiated by Buddhist monks and are closely bound with Buddhist ritual. Commanders of the SLA have to receive the blessings/imprimatur of the incumbent monk of the chief Buddhist clerical order of the country on assuming duties.

Ancient and medieval Sinhala Buddhist chronicles and traditions have entrenched in the Buddhist clergy of Sri Lanka the duty of urging on Sinhala warriors and armies to wage war on enemies of the Sinhala Buddhist nation who historically were Tamils

The Venerable Gangodavila Soma Thera, a Buddhist monk who has emerged in recent times as a widely influential ideological force, particularly among middle class Sinhalese, says in his weekly column today to the Sunday Times, the independent Sri Lankan English language paper:

"A country has a leader or a king to protect the country and its people. The king or ruler has an army to use to (sic) protect the people and not as an ornament."

"One's (the ruler's) own life and the lives of the people may be lost when one engages in battle. It is called service to the nation."

"If one is afraid or hesitant to fulfil that duty (fighting the enemy) such a person should not accept kingship. (He or she) Should not join the army. They should lead a religious life. But Buddhist literature shows instances where ascetics seeing their nation in danger leaving their robes and going to the battle field to defend their people" (Sunday Times. September 5, 1999).

Respected Sinhala scholars have explained the manner in which contradiction between the traditional Sinhala Buddhist approach to violence against enemies of the nation and the essential Buddhist concept of non-violence was mediated in ancient and medieval chronicles.

The well regarded Sri Lankan Pali scholar and historian, Prof. R.A.L.H Gunawardana (Vice Chancellor of the University of Peradeniya).

He says "The early Buddhist ideal of kingship as evident in the concept of the Cakkavatti outlined in tales like the Mahasudassana Sutta in the Pali canon, was one based on non-violence.... The attitude that the (Buddhist) Sangha should adopt towards the warrior king, the manipulator of the foremost apparatus of violence in society, would have been a problem which rankled in the mind of many a monk in the formative phase of the relationship between the Sangha and the state in Sri Lanka" Places in this context, it is possible to see in the myth of the first visit of the Buddha (to Sri Lanka) an attempt at mediating a contradiction. In the myth the Buddha is also a conqueror.

His use of supernatural powers to harass Yakkhas (early inhabitants of the island) is comparable with the king's resort to violence against foes. In explaining the need for the Buddha to take such extraordinary steps it is stated that the Yakkhas were incapable of understanding the truth and opposed to the Saasana (the Buddhist doctrine) and, therefore, they had to be removed from the island. Thus the myth presents a moral principle distinct from those found in the Pali Canon: violence is permissible in the interests of the Saasana, against those who do not understand the 'true doctrine' and are opposed to it."

"The story of Dutthagaamini in the Mahavamsa is a clear instance of this new interpretation being invoked to justify the actions of a king." (The Kinsmen of Buddha: Myth as Political Charter in the Ancient and Early Medieval Kingdoms of Sri Lanka by Prof. R.A.L.H Gunawardana. Sri Lanka Journal of Humanities. Vol.2 No.1, June 1976) Mahavamsa is a medieval Buddhist Pali chronicle which wields a tremendous influence in the formation and sustenance of Sinhala nationalism.

The ancient Sinhala ruler Dutthagaamini is celebrated by modern Sinhala nationalists. He, according to the Mahavamsa, defeated Ellaalan, the contemporaneous Tamil Saivite king of Sri Lanka, and restored the Sinhala Buddhist order.

Prof.Gunawardana says "He (Dutthagaamini) was also a warrior whose campaigns for the unification of the island in the second century B.C wrought great carnage. There was an obvious difficulty in presenting this successful warrior as a Buddhist hero. The mediation of this contradiction follows the same lines as in the myth. The campaigns of Dutthagaamini, the chronicle (Mahavmsa) asserts, were not for personal glory but for the establishment of the Saasana, to make 'the Saasana shine forth'.

According to the chronicle, Dutthagaamini was overcome with remorse at the end of his campaigns when he recalled that a multitude of (Tamil) people had been killed. A group of Arahants from Piyangudipa discerned his thoughts and came through the air to assure him that, though millions had fallen during his campaigns, he could be certain of being born in heaven.

Only "one and a half" human beings could really be deemed to have been slain by him since of all of those who had been slain, only one had practised the 'five precepts' while another had uttered the Tissarana - the three statements professing the seeking of refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha. All others were 'unbelievers and men of evil life' and were not to be esteemed more than beasts. Thus, like the myth, the Dutthagaamini legend implies that "violence committed on unbelievers (Tamils) is not evil" (R.A.L.H Gunawardana: same article. opp. cited). The Tamils are the unbelievers that the Mahavmsa consistently talks about in its annals.

Ven.Soma's preachings in the columns of the Sunday Times of Sri Lanka are subtly or openly aimed at inspiring the Mahavamsa world view as articulated by the chronicle and its later derivatives said political observers in Colombo.

The Sri Lankan Army is predominantly Sinhala Buddhist. All its official ceremonies are officiated by Buddhist monks and are closely bound with Buddhist ritual. Commanders of the SLA have to receive the blessings/imprimatur of the incumbent monk of the chief Buddhist clerical order of the country on assuming duties.

The Sri Lankan Army is predominantly Sinhala Buddhist. All its official ceremonies are officiated by Buddhist monks and are closely bound with Buddhist ritual. Commanders of the SLA have to receive the blessings/imprimatur of the incumbent monk of the chief Buddhist clerical order of the country on assuming duties.  The Venerable Gangodavila Soma Thera, a Buddhist monk who has emerged in recent times as a widely influential ideological force, particularly among middle class Sinhalese, says in his weekly column today to the Sunday Times, the independent Sri Lankan English language paper:

The Venerable Gangodavila Soma Thera, a Buddhist monk who has emerged in recent times as a widely influential ideological force, particularly among middle class Sinhalese, says in his weekly column today to the Sunday Times, the independent Sri Lankan English language paper:  According to the chronicle, Dutthagaamini was overcome with remorse at the end of his campaigns when he recalled that a multitude of (Tamil) people had been killed. A group of Arahants from Piyangudipa discerned his thoughts and came through the air to assure him that, though millions had fallen during his campaigns, he could be certain of being born in heaven.

According to the chronicle, Dutthagaamini was overcome with remorse at the end of his campaigns when he recalled that a multitude of (Tamil) people had been killed. A group of Arahants from Piyangudipa discerned his thoughts and came through the air to assure him that, though millions had fallen during his campaigns, he could be certain of being born in heaven.